ATONEMENT IN JOHN

by Roger Wyatt | 12th October 2021 | more posts on

'Word Studies'| 8

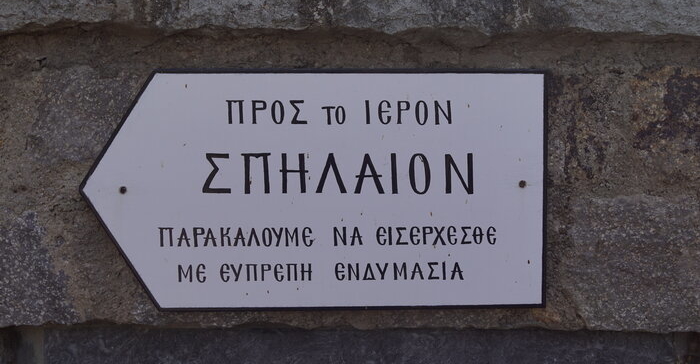

Photograph: Roger Wyatt - on the island of Patmos.

‘If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness’

The well-known verse found in 1 John 1:9 is worth memorising. It forms part of a wider exploration of the ongoing reality of sin in the life of the believer, along with a statement concerning the absolute provision of forgiveness found in Jesus Christ. That being said, Christians still suffer confusion over what Jesus actually did on the cross to forgive sin, how to appropriate that forgiveness, and most importantly what that forgiveness unlocks.

In the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, a detailed system of sacrifice was conveyed by God through Moses to his people. In fact, before any Levitical code was established sacrifice had already formed a central way in which human beings approached God; in Genesis 4 Cain and Abel are both described as bringing sacrifices to God, Abel from the flock and Cain from the field. The purpose of such sacrifices in the ancient world of the wandering Israelites were many, but within the books of Exodus and Leviticus they take on a particular function, that of atonement. In fact, prior to the more ritualistic sense in which the term is later used, in the book of Genesis, atonement has two interesting applications. In the first instance it is used to describe the pitch that Noah used to cover the ark, ‘inside and out’ (Genesis 6:14); the word וְכָֽפַרְתָּ (weḵap̄arta lit. and cover it) is employed to define what Noah did, practically, to keep the occupants of the ark away from the waters of judgement. In the second instance the term is utilised to described Jacob’s attempt to appease his brother Esau after their long estrangement: ‘For he (Jacob) thought, “I will pacify him with these gifts I am sending on ahead; later, when I see him, perhaps he will receive me”’ (Genesis 32:20). Here the word appears in the first person singular, אֲכַפְּרָה (aḵappərah lit. I will appease) to encapsulate the idea of assuaging the coming wrath of Esau. However, within the context of the tabernacle, extra nuance is added to the word:

‘For the life of a creature is in the blood, and I have given it to you to make atonement for yourselves on the altar; it is the blood that makes atonement for one’s life.’ (Leviticus 17:11)

The verse unambiguously states that it was the shedding of the animal’s blood that effected ‘atonement’, לְכַפֵּר (leḵapper lit. to make atonement) to the immediate benefit of the one offering the sacrifice. As such, the animal’s death (signified by the sprinkling of blood) would be accepted by God for the life of the one who had sinned – thus freeing the individual from the consequences of their actions. In that sense, the animal’s death was substitutionary, or vicarious. Moreover, on the Day of Atonement, described in the previous chapter of Leviticus, the High Priest would, once a year, go into the Most Holy Place, to atone for the people of Israel, and sprinkle the blood of the sacrifice onto the lid of the golden box known as the ark (described in Exodus 37) in which were found the two tablets of the ten commandments. The כַּפֹּרֶת (kapporet), sometimes translated ‘mercy seat’ or ‘atonement cover’, was quite simply the lid of the ark, but figurately represented a place of mediation between the those who had failed to keep the righteous demands of the Law and the place of manifestation of the glory of God that appeared above the cover, between the two cherubim. As God told Moses, ‘There, above the cover between the two cherubim that are over the ark of the covenant law, I will meet with you’ (Exodus 25:22).

And so, the following pattern is revealed:

CHERUBIM-----GLORY-----CHERUBIM

SPRINKLED LID OF THE ARK

ARK WITH THE LAW INSIDE

Of course, these things are later revealed to represent the very work of Christ on the cross, and in Romans 3:25 Christ is described as the one who provides true atonement: ‘God presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood’. The word used here for atonement is ἱλαστήριον (hilasterion) and is the same word found in Hebrews 9:5 to describe the lid of the ark: ‘Above the ark were the cherubim of the Glory, overshadowing the atonement cover’ (κατασκιάζοντα τὸ ἱλαστήριον - kataskiazonta to hilasterion). Theologically, the meaning is apparent, it is the sacrifice of Christ and the shedding of his blood on the cross that is, before God, substitutionary, or vicarious. It is the act of Christ’s sacrifice that brings peace, or appeasement between God and humanity. Indeed, in the next chapter of John’s letter, the apostle says as much, ‘He is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world’; what is translated as ‘atoning sacrifice’, or in some traslations as ‘propitiation’, is ἱλασμός (hilasmos), a verbal form of hilasterion, already considered above.

Returning to the wider context of 1 John 1, the language used by the apostle now takes on new Hebraic depths: ‘God is light; in him there is no darkness at all’ (1 John 1:5). It is undoubtedly the radiance of God’s glory that John here describes, and he is textually building out the relationship between the glory of God appearing above the cherubim, and the new position of the repentant believer, figuratively sprinkled by the blood of Christ. We cannot ‘claim to have fellowship with him’ (1 John 1:6) John writes, the very thing offered to Moses from between the cherubim, and yet carry the darkness of sin in our lives: ‘But if we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus, his Son, purifies us from all sin’ (1 John 1:7). The verse could easily be misread and understood as implying that ‘walking in the light’ precedes the work of purification, but in fact, the reverse is true; it is because of the shed blood of Christ that the light of God’s glory can shine into the life and heart of the believer, and indeed, those who also receive this forgiveness can enjoy together the newly available glory, in an experience known as ‘fellowship’.

Finally, it should also be said that using the term ‘covering’ instead of ‘lid’ could create some theological confusion. Whilst there is a sense that the sin of the Hebrews was only ‘covered’ and not ‘removed’, this did not nullify the reality of the appeasement that obedience to the Levitical code afforded. In like fashion, both John and Paul had a clear understanding that the death of Christ was an act of atonement, but not covering; John the Baptist clearly announced that Jesus did not come to cover sin but remove it: ‘Look, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!’ (John 1:29). And so, the strength of Old Testament atonement is best understood as one grounded in the coming atonement, to be provided by the true Passover Lamb, Jesus Christ. Atonement is then, the very means through which divine forgiveness flows; forgiveness appropriated by the faith and confession described in 1 John 1:9.