THE PROPHETS

by Roger Wyatt | 17th December 2020 | more posts on

'Getting to grips with the Prophets'| 0

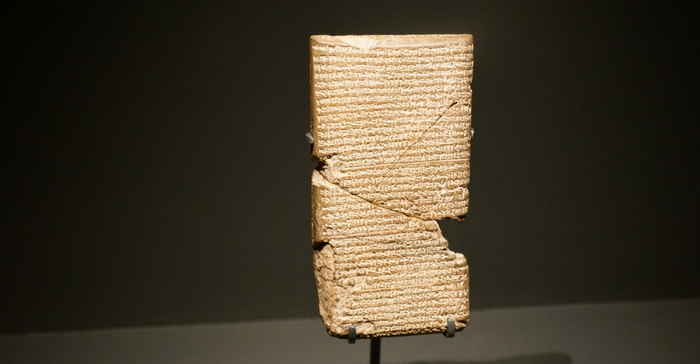

Photograph: Roger Wyatt. The Babylonian Chronicle, small clay tablet describing the Fall of Nineveh - The British Museum.

Getting to grips with the Prophets – An introduction

It can be a daunting task tackling the books of the Prophets, or the Nevi’im (נְבִיאִים) as they are called in the Hebrew bible. They are famed for their messianic prophecies, moments of poetic genius and their dramatic narrative insertions, but they are generally poorly understood. In a way this is not the fault of the reader, but rather the result of an approach to reading the Bible that has emphasised the need for daily inspiration over a serious engagement with the texts. In the end, by taking the harder route, the results are more lasting and life changing.

Modern English translations do not have an explicit subdivision known as the Nevi’im, it is generally assumed that the three major prophets and the twelve minor represent the corpus of the prophetic writings. However, the Hebrew bible includes a total of twenty one books, including Joshua, Judges, the two books of Samuel and the two books of the Kings, along with the fifteen mentioned above. The ordering of the bible in this way in fact makes more sense than that of the English bible, and reinforces my view that the prophetic writings cannot be understood without the history in which they were formed, fashioned and ultimately transmitted.

The prophetic tradition probably goes back as far as Abraham. After the Philistine king Abimelek mistakenly takes Sarah to be his wife (not knowing that she was already married), God appears to the king of Gerar in a dream and says, ‘Now return the man’s wife, for he is a prophet (נָבִיא naḇi), and he will pray for you and you will live’. The idea of “God’s prophet” would become an important one as the Israelites moved towards the land they had been promised and as the age of the kings dawned it was familiar to see prophets in the royal courts, invited and uninvited; the prophet Nathan perhaps being the most famous example for his prophetic rebuke of king David.

However, the institution of the “classical prophet” can be traced to the 9th century life and ministry of Elijah, who seemingly appears from nowhere and who like Nathan confronts the king, king Ahab, with the words: ‘As the LORD, the God of Israel, lives, whom I serve, there will be neither dew nor rain in the next few years except at my word’ (1 Kings 17:1). Elijah and his disciple Elisha therefore, were the forerunners of a tradition that would last for nearly another five hundred years. It was not however until the 8th century that those prophets associated with the prophetic writings of the bible made their entrance into the political, and social world of the divided kingdom of Israel. Indeed, the gradual decline of writing on stone or in clay was accompanied by the increased use of perishable materials like leather that did much to aid in the transmission of prophetic messages (although the Hebrew people seemed to have been writing on leather scrolls at a much earlier date). Indeed, reference to the practice of writing prophetic texts can be found in passages such as Isaiah 8:16: ‘Bind up this testimony of warning and seal up God's instruction among my disciples’. Similarly, in Jeremiah 30:2 the eponymous prophet receives a word from God instructing him to ‘Write in a book all the words I have spoken to you’. It is the practice of writing and copying these prophetic texts that, over time, formed the prophetic writings found in the bible today.

In many ways, the popular delineation between the major and the minor prophets is an unhelpful one. Whilst the three major prophets are longer, this should not lead to the assumption that the minor, shorter prophetic works are less important. The book of Zechariah is a case in point and, in my view, represents the high point of the prophetic literary tradition. Moreover, it is more useful I think to group the prophets together around the historic moments in which they lived, and their words were recorded. Such a grouping, I suggest, will help the student of the Prophets to construct a better frame of reference for the writings as they wrestle with the meaning and language of the prophetic texts.

Of course, prophecy by nature concerns what for the prophet were near future and distant future events, and as such the text is by nature decontextualised from its immediate historical context. That being said, for the most part the prophets dealt with imminent historical events which often carried a larger eschatological message - it is a prophetic device used commonly in the prophetic books; historic events operating as shadows and types of end time events. As such the prophetic writings centre around three distinct historical periods: the arrival of the Neo-Assyrians into the Levant, the rise of the Neo-Babylonians, and the period known as the pax Persiana.

The Assyrian prophets

The Assyrian prophets, as I have labelled them, were caught up in tumultuous events unfolding in the Near East in the 8th century. The rise of the Neo-Assyrian empire, with its aggressive policy of expansion, would have serious consequences for the small kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The two kingdoms were not only desirable in themselves for the invaders from the north, but the narrow strip of land they occupied was a thoroughfare to the lands of south, and especially to Egypt; which would ultimately suffer conquest at the hands of the Assyrians. Of course, the political realities hide what for the prophets were spiritual and moral ones, and the Assyrian prophets were commissioned by God to take up a message against the northern kingdom that had long departed from the way of Yahweh, embodied in the rule of a series of wicked and idolatrous kings who did ‘did evil in the eyes of the LORD’ (2 Kings 17:2). It was into this troubled kingdom that the Assyrian prophets were sent, and their message was clear - if you do not repent, you will be destroyed.

God’s nevi’im did not just operate in the north however, and during this time Judah also came into sharp prophetic focus, especially in the early prophecies of Isaiah. Isaiah is perhaps the most famous of the Assyrian prophets, he was close to king Uzziah before the kings’ death (c. 747) and he may have served in the temple where he received his heavenly call and vision. However, it was during the reign of Uzziah’s grandson Ahaz, a Neo-Assyrian sympathiser, that Isaiah’s prophetic ministry launches (the message in the south was the same as that being declared in the north; repent or a coming enemy will destroy you). In the north, also commencing their prophetic ministries in the reign of Uzziah, were Amos a shepherd of Tekoa (Amos 1:1) and Hosea, who is famously asked by God to marry an unfaithful woman to demonstrate Israel’s spiritual adultery. Micah also prophesied after Uzziah’s death, and his vision concerned ‘Samaria and Jerusalem’ (Micah 1:1) and the coming of the Assyrians.

Historically placing the book of Joel has proven to be more difficult as it does not contain the clear historical markers typical of most other prophetic writings. That being said, the prophecy does seem to primarily concern Judah and Jerusalem, with its emphasis on Zion and the temple. Moreover Joel 2:20 appears to reference an approaching northern army: ‘I will drive the northern horde far from you’. It seems probable then, although not beyond doubt, that Joel is also, like Micah and Isaiah, speaking to Judah concerning the coming of the Neo-Assyrians.

One final prophet belongs to the Neo-Assyrian period, Jonah, who delivers his prophetic message, in the end, to the city of Nineveh, the capital of the Neo-Assyrian empire. It is difficult to place the events of the short story accurately and there is some debate as to the identity of the king, described in Jonah 3:6: ‘When Jonah’s warning reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, took off his royal robes, covered himself with sackcloth and sat down in the dust’. However, the size and population of the city certainly indicates that it was the centre of the Assyrian empire and the unnamed king would have certainly predated the coming of Tiglath-Pileser III to the Assyrian throne in 745. It is my guess that he is one of the lesser predecessors of Tiglath-Pileser who struggled to keep a firm hold on the throne before the empire reached its heyday. The reference to a Jonah son of Amittai in 2 Kings 14:25, during the reign of Jeroboam II, helps narrow down when he prophesied to between 779 and 745. This would historically place the writing of Jonah close to the first half of the 8th century and it would seem prophetically fitting that God would send a messenger of mercy to the very kingdom that would soon arrive to destroy the Israelites.

The Babylonian prophets

In some ways the book of Nahum bridges the two historic time periods of the Neo-Assyrians and the Neo-Babylonians as his prophecy concerns the fall of the city of Nineveh. Despite the earlier repentance under the preaching of Jonah the city would fall at the hands of the Medes and, probably, the Babylonians in 612. It would not be the Medes however who would dominate the political landscape as the Neo-Assyrian empire collapsed, but the Babylonians.

Along with Nahum, Habakkuk can also be placed within the same historical period and God speaks to the prophet in the first chapter of the book: ‘I am raising up the Babylonians, that ruthless and impetuous people who sweep across the whole earth to seize dwellings not their own’. It is a source of grief to Habakkuk who presents his complaint to God concerning the coming enemy and God replies with a reassurance that the wicked will not go unpunished, or the righteous unsaved. Habakkuk then takes up a prophetic taunt against the Babylonians delivering five prophetic woes in Habakkuk 2, whilst the shigionoth of Habakkuk 3 describes a patient prophet waiting for the destruction of the Babylonians: ‘Yet I will wait patiently for the day of calamity to come on the nation invading us’ (Habakkuk 3:16b) – perhaps even inferring that the invasion had begun. Zephaniah is also to be included in the list of Babylonian prophets as a contemporary of Jeremiah, prophesying during the ‘reign of Josiah’ (Zephaniah 1:1).

Jeremiah prophesied in the midst of the coming calamity, ‘from the thirteenth year of the reign of Josiah’ (Jeremiah 1:2) c.627 to the ‘eleventh year of Zedekiah’, 586. The date, of course, could not be more poignant and Jeremiah’s prophetic ministry centres on the coming invasion of the Babylonians. But more than that, his prophetic message is firmly grounded on the cause of the coming exile, the idolatry of Manasseh, which despite the efforts of Josiah to reverse, would prove unsuccessful. In many ways the book of Jeremiah should pause before Jeremiah 27 when ‘early in the reign of Zedekiah son of Josiah king of Judah, this word came to Jeremiah from the LORD’ (Jeremiah 27:1). This is the moment at which the prophecies of Ezekiel commence, who around a year before, in 597, had been exiled during the second Babylonian attack on the city of Jerusalem. The young prophet priest is taken into exile and in his own words writes, ‘In my thirtieth year, in the fourth month on the fifth day, while I was among the exiles by the Kebar River’. The calling of Ezekiel, in the midst of the greatest calamity to befall the small kingdom of Judah, is significant and the young prophet’s strange ministry unfolds in the sight of all with him on the banks of the canal. It is a ministry that includes his supernatural transportation ‘in visions’ to the city of Jerusalem which is reaching its crisis point. Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles in Jeremiah 29 was most probably read to Ezekiel and the two prophets share a particular unity of purpose, albeit they may never have met. It is not until Ezekiel 33 however that news travels to Ezekiel that the city of Jerusalem had fallen to the Babylonians: ‘In the twelfth year of our exile, in the tenth month on the fifth day, a man who had escaped from Jerusalem came to me and said, “The city has fallen!”’ (Ezekiel 33:21). What was reported to the exiles in Babylon however, had to be lived through by Jeremiah, and Jeremiah 39 records the day of the fall. In the chapters that follow Jeremiah is captured released, and taken unhappily to Egypt.

Obadiah probably also lived and prophesised during the same time and his prophecy is directed against Edom: ‘Thus says the Lord GOD concerning Edom’ (Obadiah 1:1). The words of the prophecy of Obadiah are almost an exact repeat of Jeremiah’s prophecy against Edom, found in Jeremiah 49 and it is not impossible that Jeremiah either wrote the book, or sent it to Edom via the hand of Obadiah. Despite Edom’s close ancestral relationship with Judah, the Edomites proved to be treacherous neighbours for the descendants of Jacob, especially during the Neo-Assyrian period; Hezekiah called upon the Edomites for help as the Neo-Assyrian army of Sennacherib approached the walls of Jerusalem, but it was a call they did not answer. Moreover, although not well documented, according to the book Obadiah it would seem that they behaved similarly during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, and gloated over the fall of the great city.

The Persian prophets

The final prophets of the Hebrew canon are Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi, all of which prophesied during the time of the pax Persiana and rule of the great Achaemenid kings. It was forty seven years after the fall of Jerusalem when Cyrus the Great famously captures the city of Babylon, effectively bringing the Babylonian empire to an end. Fortuitously, the military success of Cyrus II in the region proved to be beneficial to the exiles in Babylon who, it was decreed in 538, would be permitted to return to Judah (the province of Yehud) to rebuild the temple. Those who returned under Zerubbabel in around 536 included two young prophets Haggai and Zechariah; sixteen years into the rebuilding project work on the temple had ceased because of opposition and both prophets were a source of prophetic encouragement to the builders, both commencing their prophetic ministries in 520. The prophecies of Zechariah however, go much further and address the future destiny of God’s people - it was a future to be marked by great tribulation, but also God’s divine help manifested in the form of a messianic figure often spoken of by the prophets. Zechariah and Haggai were contemporaries of Zerubbabel and Jeshua the High priest, who were instrumental in the rebuilding of the second temple, and both men feature heavily in the Persian prophecies.

It would be remiss at this point to not also mention Second Isaiah, as it is normally named; the second half of Isaiah’s book, from chapter 40 onwards. The prophecies relate specifically to the moment of the decree of Cyrus II, and the subsequent return of the exiled Jews to the land of promise. The final book of the Hebrew canon is Malachi, written at some point between 500 and 457 (I suggest 486). The text of this prophecy addresses the problem of a failing priesthood, and represents the last written words of the nevi’im in the Hebrew bible. They are words filled with disappointment, but also words that speak of a coming renewal, the arrival of a new prophetic era, and a new Elijah.

A recommended ordering of the prophets

Assyrian Prophets

Jonah

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Isaiah I

Micah

Babylonian Prophets

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Jeremiah

Obadiah

Ezekiel

Persian Prophets

Isaiah II

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi